The Joy of Friction

How the rejection of new technology is leading people to a happier existence

Hello and welcome to new subscribers! I’m very grateful to all who read, share, or comment on my articles—and if you’re not a subscriber yet, please consider becoming one. It’s free(!) and helps support my work.

I've come to realize the importance of technological rejection. No, not the revolutionary, smash-the-machines kind of rejection, but ordinary everyday rejection.

For example, autumn will soon be here and I'll be raking leaves again with a physical rake rather than the motorized leaf blower offered me by my neighbor. He's a retired landscaper and I don't begrudge him for using the machine himself (it probably saves him some aches and pains), but for me, there's no contest. The rake means I get to hear the wind and the birds, whereas the leaf blower sounds like a giant mosquito from outer space. I get to smell the crisp air and the leaves too, not the motor's exhaust. I get into a rhythm. I get to hear myself think.

I'm noticing other instances of rejection too. I recently took a look back through my journals and noticed how my handwriting has changed since I graduated college in 1989. The paper itself, and the ink on that paper, is a material relic of my presence from that time. A creation that says, "I was here." Direct testimony by a human hand. It’s a quality that wouldn't exist if the journals had been composed on what we then called word processors.

Explicitly or implicitly, these instances represent rejection of a newer, more "advanced" technology for an older one. A motorized tool rejected in favor of a hand tool; a digital form of writing for a form of writing that dates back thousands of years. A rejection of convenience and speed, for sure, but also a rejection of separating my body from the world it inhabits.

I'm hardly alone. Everywhere I look I see people making similar decisions, similar rejections.

A Long List of Rejects

For example, in July, I wrote about the rejection of smartphones and their addictive social media apps in favor of old-fashioned flip phones (aka "dumb phones"). I noted how people, especially teens and twenty-somethings who had been raised on a steady diet of digital distractions, were trying to refocus their attention on a world passing them by while their eyes were glued to their hand-held screens. By switching to an earlier technology they were consciously creating friction between themselves and their devices. The flip phone's limitations forced them to use it for things that were actually helpful, like making a call, and not mindless scrolling.

Another example of this trend is the stunning comeback of vinyl records. Last year, over forty million copies of the old-fashioned discs were sold, the eighteenth consecutive year of growth. Equally surprising, seven out of the top ten bestselling vinyl LPs were for new releases. While there is debate over whether vinyl recordings actually sound better than digital, there is less controversy over the reasons for their popularity. One is simply that album covers and inserts are fun to own, study, pass around, and discuss. More importantly, putting a physical record on a turntable is a more deliberate, more satisfying and social activity than just pressing a button on your phone.

Film photography is another older technology that has attracted noticeable renewed interest in recent years, with film camera sales experiencing steady growth. Alex Cooke, editor-in-chief of Fstoppers, an online magazine for photographers, notes the upsurge represents "a fundamental shift in how we value our memories." The trend represents a mindful snubbing of the shallowness that accompanies limitless posts of only your most perfect pics. Instead, Cooke says:

Film doesn't lie in the same way digital can. It shows reality, including the beautiful imperfections. This embrace of imperfection represents a growing rebellion against the hyper-polished aesthetic that dominates social media and digital photography. Film photography offers something increasingly rare in our digital landscape: authentic unpredictability that cannot be perfectly controlled or artificially replicated.

He also cites the sheer physicality of the film print, observing that when you hold a print you are holding the remnant of an actual chemical reaction that occurred when light from your subject hit the film, not some collection of 0s and 1s. For younger Millennials and Gen Z, the resulting photograph "represents not a return to the past, but a discovery of something they never experienced: the weight and presence of analog creation."

The list goes on and on.

People are choosing mechanical over digital watches for their style, authenticity, and craftsmanship, and also for what one retailer called "an antidote to the intangible nature of the digital age."

Musicians are choosing analog over digital synthesizers for their sonic warmth and expressiveness, and also for an "embodied connection" to the instrument that allows for greater creative control.

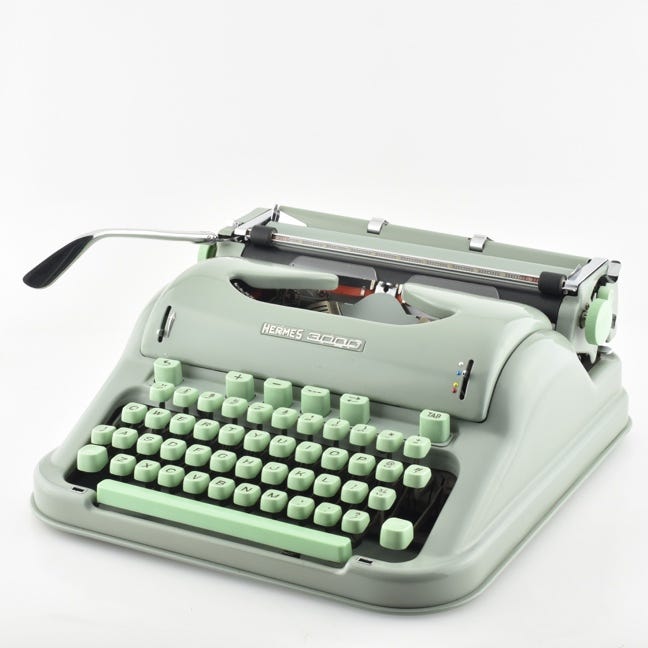

And in my own creative domain, the written word, there has been a revival of a technology I thought was surely dead—the typewriter. More than a billion dollars' worth of the clackety machines were sold last year and demand is growing. Among the reasons cited is a desire for a slower, more meditative composition process that's not interrupted by constant pings and alerts. And then there's the result: a more honest, unrevised, imperfectly human prose.

Flip phones, vinyl records, film photography, mechanical watches, analog synthesizers, typewriters... What's going on here?

Friction, Authenticity, and Noiselessness

I would suggest at least three things. The first is "friction," which Merriam-Webster defines as: the rubbing of one body against another. Implicit in this definition is physicality. You and I have a physical body. ChatGPT and Instagram most certainly do not. In all the pre-digital technologies above, the human body is far more engaged than with its more recent counterpart. For example, among the comments I often found while researching flip phones was how much users enjoyed the simple feel of its buttons and the click sound of closing it. The tactile pleasures of vinyl records, paper photos, and typewriter keys were regularly cited by their respective users too.

The frictional difference between two technologies can be relative as well, as in my opening example. Both the rake and the leaf blower require my physical control, but the rake becomes a direct extension of my body such that the energy of my muscles' movement and rhythm is transferred directly to the leaves. We enter into a sort of dance. The leaf blower, on the other hand, is not a very good dance partner.

Another frequently cited reason to prefer earlier technology could be summarized by the word "authenticity." These technologies make people feel more authentically human by allowing more room for mistakes and surprises. Users of film cameras note that only having a limited number of exposures to a roll forces them to value each shot, and to appreciate the imperfections they discover after the film is developed. Authenticity also arises by interacting on a more human timescale. Texting on a flip phone, for example, is more cumbersome and encourages more care and reflection on the part of the texter.

And then there is the greater "noiselessness" of low-tech/slow-tech alternatives, and I'm not even talking about being spared the mind-numbing sound waves of a leaf blower. I'm talking about the reduction in mental noise. When a vinyl record is playing on a turntable, you just let it play and don't wonder about what your algorithm will choose next. A mechanical watch on your wrist means one less reason to consult your phone and react to its notifications. Indeed, the elimination of social media "noise" was the number one benefit cited by flip phone users.

Friction. Authenticity. Noiselessness. These once underappreciated benefits of older, simpler, more human-scaled technologies seem to be addressing one of the most written about and agonizing problems of modern life—alienation. As the Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich argues in Tools for Conviviality, his 1972 treatise that reimagined modern society, we thought machines could do unremitted work, work that was once done by enslaved people. But the machines enslaved us instead. He goes on to say:

The crisis can be solved only if we learn to invert the present deep structure of tools... People need new tools to work with rather than tools that 'work' for them. They need technology to make the most of the energy and imagination each has, rather than more well-programmed energy slaves.

Making the most of a user's energy and imagination is exactly what human-scaled technologies do, and they are making themselves felt throughout our culture in many small ways. This, of course, is much to the chagrin of a tech industry that practically screams at us to always buy the next shiny object. And I haven't even touched on generative AI, the shiniest object of them all at the moment. More on that in a future essay. For now, the crisp morning air is calling and I'm heading out to the tool shed for some authentic work.

Walks without earbuds, nights without streaming services—there are so many blessings we can tap into when we slow down and turn the machines off. Wonderful sentiments!